In 5.5 days, we only saw 1 human being: I saw Glenn and Glenn saw me.

For all we know, for most of that time we were the only humans in the 252,500 acres (1022 km2) Mazatzal Wilderness (Mazatzal meaning Land of Deer in Aztec, even though the Aztecs aren’t supposed to have come this far north), especially given that the 8.5 mile park access road is closed to traffic and the wilderness is wild precisely because it’s a very tough place to get into.

Day 1 was brutal. We set off from LF Ranch under the weight of approximately 45 pounds (20.5 kilos) on each of our backs; mostly 2 days’ water, 6 days’ food and the compulsory emergency rations. We walked out of the front of LF Ranch and almost immediately started climbing… and it just became steeper, narrower and more overgrown as the views became more spectacular and LF Ranch tinier with every step we took… We hauled our packs up 4000 feet (1333 m) over five miles, 6 hours and several small, light brown tarantulas, collapsing a mile later at a pretty camp spot by a dry wash, under a mountain lion-friendly looking 100+ year-old tree.

Day 2 took us up, down ‘n all around an assortment of steep hills, via a dry creek, where we competed with the flies, wasps, water insects, larvae and a few potential killer bees for six of the remaining nine or so litres of water in a rock puddle just before a pine forest area torn up by a tornado. It’s a good job we found that puddle, because we would have run out of water a day before the next puddle. After being saved by the compass at an unmarked trail intersection which I labeled with ephemeral pebbles and stick arrows which will probably wash sideways with the rain and confuse the next unfortunate hikers to reach that spot, we camped in a pine forest at the foot of a peak we hoped we didn’t have to climb the next day.

Day 3 started badly. We found a lonely Arizona Trail marker behind a bush at an intersection and made the mistake of assuming it was pointing in the right direction. After over an hour fighting our way through thick undergrowth, wild washes and fallen trees, following half-hearted stone cairns and scraps of rotted plastic markers in trees, we realised we’d gone the wrong way… so we had to turn around and fight our way back through thick undergrowth, wild washes and fallen trees, following half-hearted stone cairns and scraps of rotted plastic markers in trees in the opposite direction. We’d lost 2 precious hours of daylight and a lot of energy. In a frantic fury and a cloud of dust, we built a proud new cairn in record time and planted the marker pointing the way it always should have, watched by four black and white woodpeckers taking a break from drilling holes in some dead trees, to save future equally gullible hikers from the same fate.

Once found, the trail lured us up a steep slope to an outlook with impressive views of the San Francisco peaks, poking up above the Mogollon Rim, which we had hiked through before Flagstaff and the break for Glenn’s shin splints to heal, many moons ago. Sitting there, under some kind of a holly tree next to a bright red rock outcrop, thanks to Glenn’s brother Phil and a glimmer of mobile coverage, we learnt the fantastic news that Obama is the not-so-new new president; a relief not only because he won, but because we didn’t want to be the only people in the US not to know who the president was.

More uphill and we reached a solid stone ledge decorated with bulbous clumps of cacti, and polished by time, with views of range after mountain range fading into the smokey hazy blueness on the horizon. From there, we wound down the other side of the hill towards a dot on the map labeled Hopi Springs, where we hoped to find water. We crossed one dry but washed out creek after another and the two miles to Hopi Springs came and went, leaving us with a worried feeling parching our throats. A couple of despondent bends later, though, and we stumbled across an Arizona Trail marker hidden by 3 litres of filtered water kindly left for us a few days earlier by Shawn, the lady hiking the trail for MS. A great camp spot below turned out to be next to an enormous solid stone slab in a dry creek with wondrous potholes filled with water and happy looking little creatures swimming around leisurely. We camped, drank the water left for us and tanked up our waning 13-litre supply. We’d later be able to confirm that we’d camped at Horse Seep Camp, where Maryann of LF Ranch had rightly predicted that we’d find water.

Day 4 tore at our arms and clothes. The trail contoured the mountains past century plants scattering their seeds from their 12-foot (4-metre) high pods for a few miles, offering views of rock chimneys and unlikely, vivid colours in the mountainside, but the further we went, the more plants had larger thorns waiting to ambush our ankles and arms. After a long but gradual climb, we popped out on a saddle with a confusing sign and another tarantula before launching ourselves again into a tangle of vines and roses gone wild, presumably belonging to a long-abandoned homestead. We eventually emerged onto a summery ridge with stunning views of the valley 6500 ft (2166 m) below on one side and the spectacular rocky outcrop of the 7903 ft (2409 m) Mazatzal Peak on the other. We disinfected our impressive collection of scratches, ate lunch, admired the views, took photos and sunbathed… before noticing a high wall of cement-like cloud heading towards us at eye-level and frightening speed.

We stared at the steep, tiny, tangled, 2-mile trail precariously hugging the foot of the Peak on the one side, back at the solid cloud wall on the other, then back at the Peak trail again, like a cat watching a ping pong match. When the ball finally dropped, we suddenly realised we needed to make a frantic dash across the Peak before the weather hit or risk being stranded on a high rocky ledge, slippery when wet, in forceful winds, rain, snow and maybe lightening. We threw our gear back in our packs and lept head-first into the matted and thorny plant tangle protecting the trail from hikers, racing against the clock and the approaching wall of Winter.

Fifty minutes later, just as the downpour started, we made it to the relative safety of the mountain shoulder, waterproofed ourselves and our gear, caught our breath and headed over the other side of the hill, down a steep, never-ending, V-shaped switchback lined with soggy yellow and russet oak leaves and occasionally blocked by fallen trees killed in a fire some years ago, finally reaching Bear Spring, probably named for good reason, where we found a sheltered camping spot.

While I spent the night counting the seconds between thunder and lightening, scaring myself in the eye of the circling storm, wondering whether the hollow metal rods holding up the tent -the only metal for 40 miles around- would make us a lightening magnet and whether we should be adopting the lighting survival crouching position outside in the downpour, while listening to the wind whoosh and grow to a thundering howl as it swept up the valley behind us in slow motion and slapped the tent, Glenn snored peacefully beside me.

It’s day 5, I’m sleep-deprived, it’s still raining heavily and the 6500 ft (2166 m) mountain we’re on is shrouded in thick fog stirred by an angry wind. We feel very exposed, but our first priority, as ever, is to get drinking water. So, we hike the 400 yards (365 m), through dank, orangey autumn ferns to Bear Spring’s spring box, a well-like, rock-built pool of spring water, which we pump and sterilise as fast as our equipment and muscles allow. After some snack bars and speedy, wet backpack packing, we scramble up the next hill, fighting dripping, thorny plant-life. We have to climb back up to 7200 ft (2400 m) before we can start to drop down below the cloud line, and we need to do it fast, before the weather gets any grimmer. The trouble is that we have to scramble up through several miles of dead trees, swaying, creaking, groaning and occasionally slamming to the ground in the high winds around us, before we’re allowed to start the long downhill trek… and it turns out that a good chunk of the early downhill is along a muddy ledge slippery with wet leaves, lined with trip traps, with a vertigo-inducing fall-off to our immediate left. Glenn has to talk me and my fear of ledges through some of this, but we finally reach a lower, clearer stretch of trail where it’s stopped raining and we can make good time. We’re racing now: we need to cover 14 miles today to be sure of getting out of the Mazatzals tomorrow, and it’s going to be very tight.

Several hours later, after a long switchback descent near Mount Peeley trailhead, we head to the start of the final trail passage, descending into a wash which is so ripped up by previous wild water at least 15 ft (5 m) deep that it looks straight out of a movie set about a gruesome end of the world, but right now it has just a small stream down the middle of it and a very eerie feeling, especially given that sunset is soon and I know it’s going to start raining again as soon as the temperature drops. What’s more, despite fancy new Arizona Trail signs popping up here and there, the trail disappears into the wash. We’re exhausted, the contour lines are all merging together on the map and we’ve only covered 12 miles, but we can’t find the way forward and can’t risk getting swept down the wash when it starts raining, so there’s nothing for it but to hike half a mile back up the trail we came from to a previously used camp spot we saw on higher ground.

We pitch the tent and it almost immediately starts raining, then pouring. We hang our food bag up on a bear-unfriendly branch above the trail, figure out where the missing trail’s hiding, sleep for about an hour, then wake up, as if slapped with a wet fish, to the sound of a creek flowing next to the tent, where the trail had been before. It sounds worse than it is, but it’s less than 9 ft (3 m) away and the rain’s torrential and swearing never to let up. I sleep for another few minutes, this time waking stunned to a river where the creek had been before. Are we in the main drainage path of the Mazatzals?

Our only food is now hanging above fast-flowing, fast-swelling flood water. 23.00h, the rain’s getting stronger and I’m thinking we need to hike back up the edge of the trail and out to the trailhead before it becomes completely impassable and we’re stuck between the drainage water and the wild wash below. Glenn thinks it’s too dangerous, so he braves the storm to rescue the food bag, which thunks him on the head when he releases the knot, while we digest our unappetising options. We pack the contents of the tent, so we’re ready to make a dash for it. We certainly can’t stay where we are without risking getting flash-flooded away, so Glenn finds us a water-free rocky patch about 15 ft (5 metres) above the impromptu river. We unpeg the tent and move it wholesale up the hill. Inevitably, though, the fly sheet rubs against the inner tent, soaking both it and patches of our sleeping bag. Despite our waterproofs, our boots, socks and some of our clothes also get wet as we battle the torrential rain and wind to re-peg the tent higher up the hill. We climb back in the tent, take off our wet clothes and manage to get fairly warm, even if we don’t get much sleep, as we’re listening to see whether god’s going to keep filling the bath or pull the plug. It really is very rocky and sloping, so we keep sliding down the tent. We’re not 100% safe, but we are safer and my gut stops screaming “RUN” at me.

Day 6 finally dawns and it stops raining, so we scrape ourselves off the rocks, put our wet and not so wet clothes back on and stick our head out of the tent to find that the river’s subsided, but it has snowed and it’s deep freeze icy, especially in wet clothes. We’re still at around 6000 ft (2000 m) afterall. We pack up as fast as we can, but I’m getting dangerously cold. I can’t feel my fingers and part of my hands at all and even my thoughts are starting to freeze, so I have no option other than to start hiking like a crazy thing to warm myself back into life. It takes a mile of steep, wet and rocky uphill, but I’m finally alive enough to feel hungry and eat a snack bar.

The trail we were supposed to take crosses the wild wash 20 or so times, so although we were now fairly sure we knew where it was, it was probably impassable and we needed to reach somewhere we could dry off, thaw out and get some sleep, so we headed back to Mount Peeley trailhead and the 10-11 miles along the forest roads, currently closed to motor vehicles, which roughly followed the Arizona Trail and was our quickest way out to the highway, with Winter snapping at our behinds.

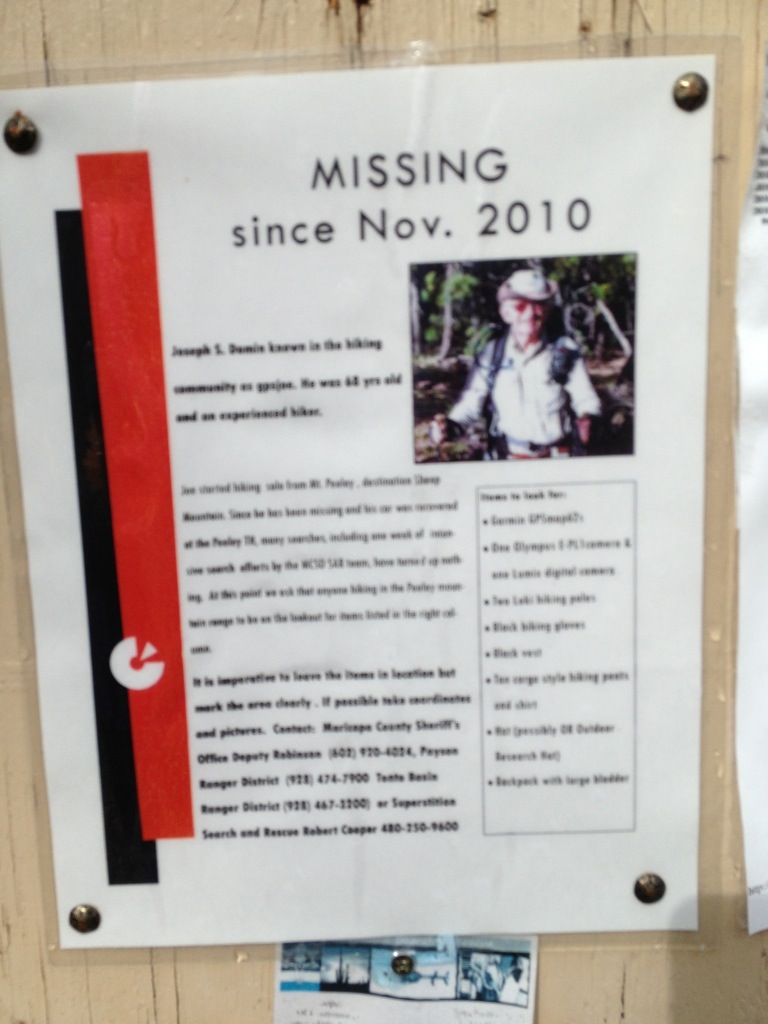

At the trailhead, a picture of a 60-something year-old hiker who’d gone missing about a year ago, leaving only his car despite extensive searches, spelled “R•E•M•O•T•E A•N•D D•A•N•G•E•R•O•U•S” and reminded us that we hadn’t seen a soul, except for each other, for over 5 days, a town and clean clothes for 9 days.

The forest road, which we expected to drop us down and out of the bad weather quickly and efficiently just kept climbing and climbing, gnawing at our exhausted calf muscles. It took 6 miles, to start losing serious height. After 7 miles, we saw and stared at our first human for 5.5 days; a bear hunter trying to recover a charred game camera, with an enormous pistol strapped to his side. After 9 miles, we walked into coverage and were able to arrange for Denis, the owner of the A Touch of Class taxi service to pick up these two wet, muddy, stinky and very grateful hikers in his plush, leather-upholstered ride and drive us 30 miles, as we marvelled out the window at the fast-moving scenery, to the seeming metropolis of population 14,000 Payson.

The Mazatzals had embraced us, stunned us with their beauty, then betrayed us, thrown us in the cold cycle with mud for detergent and spat us out wet and stunned at mile 222.5 on Highway 87, in the middle of nowhere. I wouldn’t have missed them for anything.

Absolutely stunning epidsode of your challenging hike…and an absolutely stunning, well-written story!! What a master of words you are, Francoise!!!! Thank you for sharing your journey with us and telling such an honest tale of your experiences! Wonderful!!!!